Louis Armstrong

The Queens Museum of Art, Queens, New York, September 23, 1994-January 8, 1995

Museum of African American Life and Culture, Dallas, Texas, January 21-April 2, 1995

Terra Museum of Art, Chicago, Illinois, April 15-June 25, 1995

Stedman Art Gallery, Rutgers University, Camden, New Jersey, August 7-October 7, 1995

New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, Louisiana, October 28, 1995-January 7, 1996

Strong Museum, Rochester, New York, January 27-April 7, 1996

Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences, Savannah, Georgia, April 27-July 7, 1996

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C., July 27-October 6, 1996

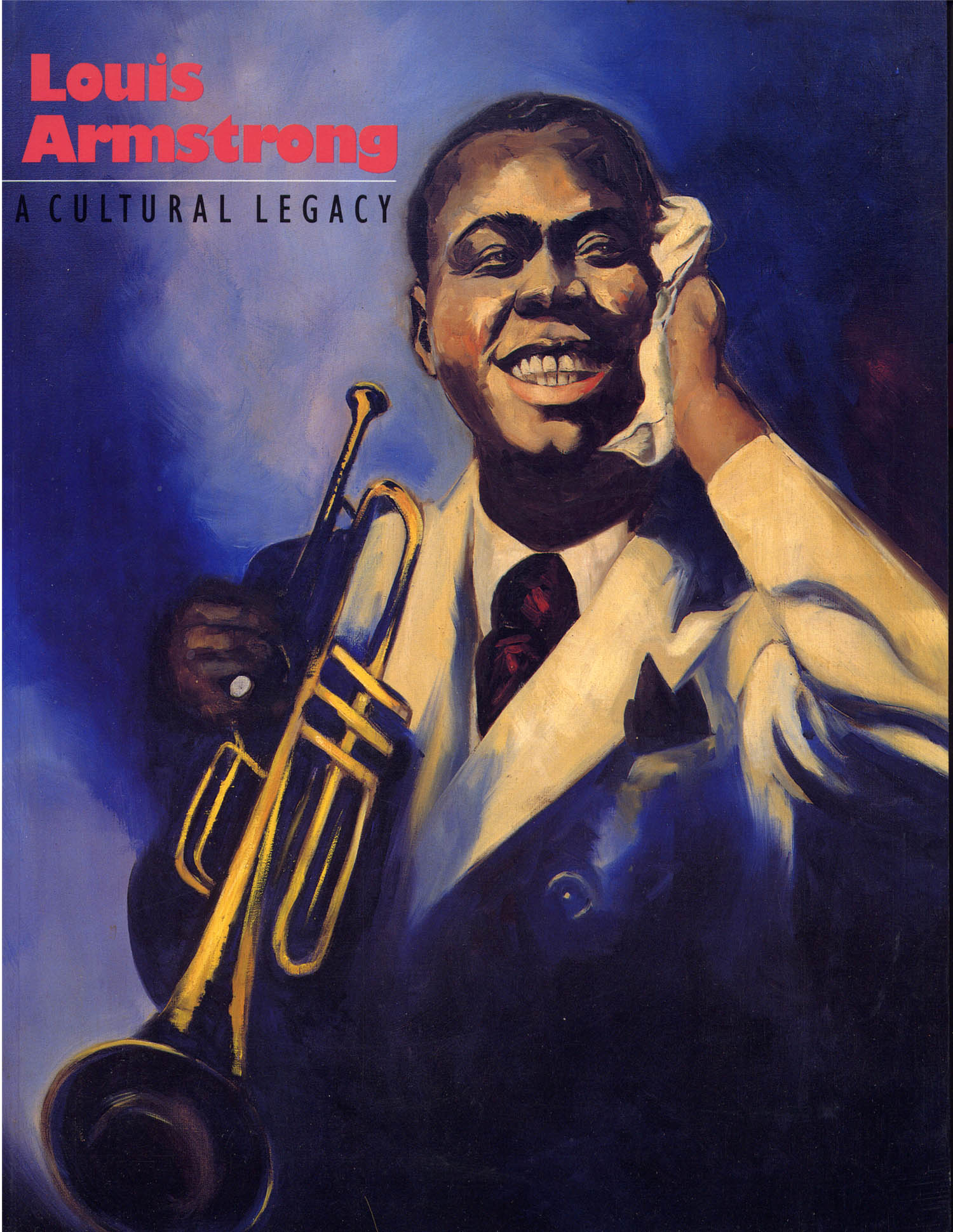

Catalogue for Louis Armstrong: A Cultural Legacy (University of Washington Press, 1994). Painting by Calvin Bailey (1948) after a photograph by Anton Bruehl. Painting owned by the Louis Armstrong House.

I can still remember the phone call from Phoebe Jacobs, trying to interest the Queens Museum in organizing an exhibition about the jazz musician Louis Armstrong. For almost thirty years Armstrong had lived in a modest house in Corona, Queens, about a mile from the museum. Phoebe was the vice president of the Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation, then in the process of turning over Armstrong's house and collections to Queens College.

Given Armstrong's incredible stature today, it's hard to believe how little serious attention he received in the 1980s. Most Americans associated him with the television appearances he made toward the end of his life, where he seemed like a relic of some distant age. It took Phoebe several phone calls to convince me to do the exhibition and it took me several attempts to persuade the museum that it could be done in a way that conformed to the museum’s mission to exhibit visual art. Louis Armstrong: A Cultural Legacy told Armstrong's life story by combining documentary photographs, ephemera, and memorabilia with fine art that more broadly expressed the spirit of jazz and the importance of African-American culture. The exhibition got major funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Fund. We teamed up with the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) to travel it to seven venues, including the National Portrait Gallery and the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Armstrong had been a consummate pack rat, saving scrapbooks, photographs, records, tapes, letters, manuscripts, instruments, and awards, all of which I browsed through in unmarked boxes at the Santini Brothers warehouse. It was exciting to learn that he was a creator of collages, working with whatever photographs and scraps of paper surrounded him. In those days, before the art world emphasized inclusivity and multi-culturalism, it was surprisingly easy to borrow major works by African-American artists, many of which were in museum storage or still for sale in galleries. The Armstrong exhibition featured photographs by Arthur P. Bedou, Villard Paddio, and Gordon Parks and art by Archibald Motley, Jr., Romare Bearden, and Jacob Lawrence. There were also works by Jules Pascin, Stuart Davis, Irving Penn, Ben Shahn, and many others.

Curating the exhibition was a formative experience for me. I was greatly helped by a number of advisers, who contributed to the exhibition and its catalogue: Richard A. Long, who wrote about Armstrong and African-American culture; Donald Bogle, who wrote about Armstrong on film; and jazz historian Dan Morgenstern. Especially important was the scholar Albert Murray, brought in by SITES project director Marquette Foley. During meetings at his apartment in Harlem, Murray showed me how inextricable African-American culture is from American culture and stressed the need to present Armstrong within that broader history and not just within the confines of jazz. For Murray, Armstrong was the equivalent of Picasso, Joyce, Chaplin, Stravinsky and the other great creators of modernism.

Invitation to the opening of "Louis Armstrong: A Cultural Legacy" at the Terra Museum of Art, Chicaog, Illinois

Invitation to the preview for "Louis Armstrong: A Cultural Legacy" at the New Orleans Museum of Art

Invitation to the opening of "Louis Armstrong: A Cultural Legacy" at Rutgers University, Camden, New Jersey

Exhibition Guide for Louis Armstrong: A Cultural Legacy, Queens Museum, 1994

Queens Museum exhibition guide

Queens Museum exhibition guide

Louis Armstrong and the Queens Jazz Trail

Tony Millionaire, "The Queens Jazz Trail" (Flushing Town Hall, 1998)

E. Simms Campbell, "A Night-Club Map of Harlem," 1932

One of my favorite objects in the Armstrong show was E. Simms Campbell's 1932 nightclub map of Harlem. I would recall it later on, when Jo Ann Jones, the director of the performance venue Flushing Town Hall, recruited me to curate a series of jazz exhibitions. Besides Armstrong, the borough of Queens had been (and still was) home to countless jazz musicians. In conjunction with an exhibition on the bassist Milt Hinton—then the senior figure of the borough's jazz community—we published an illustrated map, like Campbell's, showing Queens musicians' homes and hangouts.

The Queens Jazz Trail map drew attention to a previously ignored world of celebrity. Flushing Town Hall set up bus tours to trace its paths, and a rush of press ensued. British travel journalists selected the map as an honorable mention for the year's best new tourist initiative. Years later, it helped lead to the land-marking of Addisleigh Park, the ten-block area in St. Albans, Queens, where Count Basie, Billie Holliday, Ella Fitzgerald, Fats Waller, James Brown, Milt Hinton, and many, many others lived. The map became the starting point for my next enterprise, Ephemera Press, a small company that published illustrated cultural maps of New York City neighborhoods.