Related Groups

Page 5 of 16

ABC No Rio Dinero: The Story of a Lower East Side Art Gallery

Edited by Alan Moore and Marc Miller

New York: ABC No Rio with Collaborative Projects, 1985

Fashion/Moda

When ABC No Rio came into existence its closest parallel was Fashion/Moda, a South Bronx art space founded in fall 1978 by Colab member Stefan Eins. The two spaces shared the same "interactive" ambitions and often featured the same artists. A recent émigré from Austria, Eins was a font of new ideas. In 1971 he opened the 3 Mercer Street Store in Soho, a storefront where the concepts of "art" and "merchandise" were fused in ways that looked forward to Colab's "A. More Stores." His decision to create a gallery in the poverty-stricken South Bronx created a bridge that joined the downtown art scene with distinctively different cultural trends in the Bronx and outer boroughs. Many young artists were affected by the intermixing, perhaps none more than the Ahearn twins, both members of Colab. John Ahearn's painted plaster casts of South Bronx residents were acclaimed in both the Bronx and Soho. Charlie Ahearn's independent film "Wild Style" captured the spirit of the nascent South Bronx hip-hop scene and helped launch art careers for graffiti artists like Sandra "Lady Pink" Fabara, Lee Quinones, “Fab Five Freddy” Brathwait, John "Crash" Matos, and Chris "Daze" Ellis, all of whom showed at Fashion Moda. Many people contributed to Fashion/Moda’s success. The gallery's co-directors included William Scott and Joe Lewis (now a respected educator as well as artist). Photographer Lisa Kahane recorded many of the activities at Fashion/Moda and documented its South Bronx neighborhood. In 1980 artists from Fashion/Moda were featured in an exhibition at the New Museum that helped publicize and spread the trend of a new multicultural aesthetic and politicized community art. We included articles about that show in the No Rio book.

Fashion/Moda at the New Museum (Excerpts)

By Steven Vincent, East Village Eye 1980

A varied crowd attended the opening of Fashion/Moda's new show, "Events": preppies pronouncing every word as if their lips were pursed into permanent sphincters, new wavists in black leather and prismatic hair dye, spiffy art aficionados out to find the Latest Things, press photogs, Rastafaris, and street-hip black kids seeing work meant for them as much as for the crowd on upper Madison Avenue. The lobby of the New School for Social Research is cluttered with congested ash-trays, half-full beer bottles, knots of people discussing topics as diverse as the names scrawled on the inside of a subway car. There's a party atmosphere at the show that's been billed as "The Death of Modern Art."

That's Stefan Eins' quote. He's the Austrian-born founder of the South Bronx collective, Fashion/Moda. On the night before the opening he takes time out from hammering together an art piece to explain the concepts behind "Events." With him are Fashion/Moda artists Joe Lewis and Marc Brasz.

"Modern art, especially abstract art, is a dead-end street," Stefan comments from beneath his Joseph Beuys-like fedora. Modern art shows," continues Marc Brasz, "have always been the selection of the best of a certain group. This show represents a wider circle."

Joe Lewis adds another objection to the established modern art scene: "It caters to an elite group of wealthy people."

..."Fashion/Moda exhibits different cultures coming together. We included non-white, non-Western influences, and we're exhibiting artists from New Orleans and West Oakland." Lewis draws attention to the signs written in four languages- "English, Chinese, Russian and Spanish-the major languages of the world."

...One idea the Fashion/Moda artists are committed to is access. Speaking of the efforts of non-established artists to create their own exhibits, thereby avoiding mainstream galleries, Joe Lewis says, "There has never been a time when galleries haven't choked off younger artists. Galleries play it safe, go for the sure thing. And that stops growth. They turn art into capitalism." "This is a totally non-money conscious show," Stefan adds.

Fashion/Moda director Stefan Eins (center). Eins is depicted in the John Ahearn cast second from the left; the two men flanking him are depicted in the double cast at right. Photo by Lisa Kahane

But accessibility is more than just a space in which to exhibit art; here it means the art work itself. It's accessible. Representation is back. Gone are murky, quasi-mystical abstractions, non-referential psychology, sterile conceptuality. This art reaches out to you, smashing notions of subject/viewer dialectics; it seems to thrive on being seen and enjoyed rather than hiding, hoping to lure the viewer into its field. One thinks immediately of the ultra-public art found on subway cars.

...The Fashion/Moda people say they want nothing to do with concepts, labels, or schools. Criticism is out. As Marc puts it, "This show is a vast array of compulsiveness. How can you say one compulsion is better than another? That's like saying one person is better than another." Later, he adds: "Quality is no longer an issue. Quality is the concern of abstract art." Joe Lewis says it another way. "At a time when the situation in politics, economics, science, is separating people, we are trying to pull them together by incorporating all things."

Something new is going on. Art is enjoyable again, packing a right to the gut rather than a titillation to the edge of conscious-ness. You can feel this stuff without turning your brain inside out, or worrying about saying the right thing.

Graffiti opening in 1980. Photo by Lisa Kahane

Areial view of Forrest Avenue Maze in a South Bronx schoolyard. Photo by Lisa Kahane

Kids at the Forrest Avenue junior high school in the maze. Photo by Justen Ladda

Collage by Wesley Sanderson appearing in the East Village Eye's Christams, 1980 issue. Marc Brasz's paintings are visible at upper left; below them L'il Hot Stuff gritting his teeth with the logo "Don't Buff the Stuff" (the New York City Transit Authority routinely strips graffiti from subway trains using a powerful solvent called "the buff"); at right are casts by John Ahearn; below them an image of a man in the trainyards by Lee Quinones; images of jazz musicians by different photographers; at lower left a painting by Robert Colescott

Group Material

Soon after ABC No Rio opened in 1981, a storefront gallery was started nearby on East 13th Street by Group Material, a collective of young artists that included Julie Ault, Mundy Mclaughlin, Tim Rollins, and later, Doug Ashford and others. Like No Rio and Fashion/Moda, Group Material was committed to an interactive model that placed the emphasis on art rooted in cultural exchange and politics. More programmatic (and much better organized) than No Rio, Group Material diligently renovated its rented space and mounted an ambitious series of theme exhibitions exploring subjects like AIDS and gender. The Group Material gallery storefront closed after one season, but the collective continued to produce a variety of pointedly political exhibitions in different art spaces and unusual locations, such as poster shows on buses and subways. Because the artists at Group Material faced many of the same challenges that No Rio faced, we included in the No Rio book an essay by Group Material explaining their decision to close their storefront. The book also spotlighted the early work of Tim Rollins, whose work as an art teacher in the South Bronx exemplified a particular form of interactive collaboration with children. In recent years Julie Ault has continued to promote the ideas of Group Material, No Rio and related groups in books like Alternative Art New York, 1965-1985.

Caution! Alternative Space! (Excerpts from Handout)

By Group Material, 1982

Group Material started as twelve young artists who wanted to develop an independent group that could organize, exhibit and promote an art of social change. In the beginning, about two years ago, we met and planned in living rooms after work. We saved money collectively. After a year of this, we were theoretically and financially ready. We looked for a space because this was our dream-to find a place that we could rent, control and operate in any manner we saw fit. This pressing desire for a room of our own was strategic on both the political and psychological fronts. We knew that in order for our project to be taken seriously by a large public, we had to resemble a "real" organized gallery. Without this justifying room, our work would probably not be considered art. And in our own minds, the gallery became a security blanket, a second home, a social center in which our politically provocative work was protected in a friendly neighborhood environment. We found such a space in a 600 square foot storefront on a Hispanic block on East 13th Street in New York.

We never considered ourselves an "alternative space." In fact, it seemed to us that the more prominent alternative spaces were actually, in appearance, character and exhibition policies, the children of the dominant commercial galleries. To distinguish ourselves and to raise art exhibition as a political issue, we never showed artists as singular entities. Instead, we organized artists, non-artists, children--a broad range of people--to exhibit about special social issues (from Alienation to Gender to The People's Choice, a show of art from the households of the block, to an emergency exhibition on the child murders in Atlanta).

...Externally, Group Material's first public year was an encouraging success. But internally, problems advanced. The maintenance and operation of the storefront was becoming a ball-and-chain on the collective. More and more our energies were swallowed by the space, the space, the space. Repairs, new installations, gallery sitting, hysterically paced curating, fund-raising and personal disputes cut into our very limited time as a creative group who had to work full-time jobs during the day or night.

People got broke, frustrated and very tired. People quit. As Group Material closed its first season, we knew we could not continue this course. Everything had to change. The mistake was obvious. Just like the alternative spaces we had set out to criticize, here we were sitting on 13th Street waiting for everyone to rush down and see out shows instead of is taking the initiative of mobilizing into public areas. We had to cease being a space and start becoming a working group once again...

If a more inclusive and democratic vision for art is our project, then we cannot possibly rely on winning validation from bright, white rooms and full-color repros in the art world glossies. To tap and promote the lived esthetic of a largely "non-art" public-this is our goal, our contradiction, our energy. Group Material wants to occupy the ultimate alternative space-that wall-less expanse that bars artists and their work from the crucial social concerns of the American public.

The People's Choice (Excerpt)

By Elizabeth Hess, Village Voice, 1981

"Arroz con Mango" installation view, a Group Material show of art and personal treasures gathered in the neighborhood

Group Material is run by a collective of recent art student graduates who decided to organize before the inevitable middle age art world depression sets in. Their procedures are an implicit critique of the dominant mode: they send out flyers and put up posters that announce their upcoming theme shows, inviting anyone to enter a piece of art. For "The People's Choice," their current show (later renamed "Arroz con Mango") the members went door to door on their block (13th Street), and asked each household to donate a valuable possession; everything that came in went up on the walls. It wasn't so much that they wanted "art," as anything with "sentimental, cultural value."

...The mix of people lying on 13th Street is evident from the variety of items. In between the religious icons and fetishes is a cover from Interview magazine, a signed Warhol photograph, and a red Duchampian dustpan on the floor, contributed by Tim Rollins, a member of Group Material. Two others, who also live in the neighborhood, contributed a cover from the New York Post. The headline reads: "ROCKY DEAD, COLLAPSES WITH HEART ATTACK WHILE WORKING ON A NEW BOOK." This certainly is a collector's item. But one wonders whether or not these artists would submit the same work to other shows.

Has this exhibit really affected the collective's notion of what is art? Will the folks on the block really dictate the esthetic at Group Material? I worry that there is a touch of liberal guilt here, of getting down with the community they have just moved in on. I hope this show will breed cross-fertilization among its contributors. What does Norma Fernandez, who created "Rope Man" ("I made this in high school when I was 15. It has a horsehair head. It looks like my ex-husband"), think about Rollins's beautifully designed dustpan as a tool, as a metaphor, as an object of significant art?

For the moment, "the people" are deciding what is valuable art-not Hilton Kramer or Armand Hammer-on 13th Street.

Who's Teaching What to Whom and Why

By Tim Rollins, Upfront, 1983

Roberto Ramirez, working in classroom at I.S. 52, 1982. From Tim Rollins and K.O.S. A History, edited by Ian Berry, Tang Museum, Skidmore College, MIT Press

Rollins:... I don't consider myself an art teacher, per se, because I am interested in developing a new method of understanding the world. I consider myself to be, quite literally, an artist who works in the medium of education. I tend to go in with concrete serious art projects that we do as a group, collaboratively. In a way, I think my greatest success is that I've pulled kids into the realm of production, where they make real things that other people see, which is unusual in school, and they get feedback from it.

...We take concrete materials like bricks, and from bricks we learn about arson...we go down to the Fire Department...The firemen sees these ten crazy kids and me come stomping in asking, "Why are there so many fires?" and one of them gives us an answer.

Then we go into an abandoned lot where a building has just been burned. We all take bricks and go back to the classroom. I say, "Stare at a brick for five minutes and try to pretend the brick is an old person who's been through a lot of shit and wants to tell you all about it." And so they stare at it. I don't know who got the idea first, but we start turning the bricks into little tenements I asked the kids to write a reason, "Why you think the place was burned." We got 70 different reasons and it was beautiful. Some did say junkies burned the buildings down, but then they wrote things like "no heat," which is what the fireman said: "When the landlord doesn't provide adequate heat, a lot of people overload their circuits and the place sets on fire...

Untitled (Bricks), 1982-83, Tempera, acrylic on found brick. Collection of Peter Stern, courtesy of the artists and Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York; Courtesy of Brook Alexander; Collection of David Deitcher; Collection of artists, Installation view, ICA Philadelphia, 2009. From Tim Rollins and K.O.S. A History, edited by Ian Berry, Tang Museum, Skidmore College, MIT Press

Untitled (Bricks), 1982-83, Tempera, acrylic on found brick. Courtesy of Brook Alexander, New York. From Tim Rollins and K.O.S. A History, edited by Ian Berry, Tang Museum, Skidmore College, MIT Press

Group Material's Subway Poster Show

By Glenn O'Brien, Artforum, 1983

Group Material has taken the graffiti writer's struggle for a human environment to another stage. This group of artists put art on the subway, not by the illegal decoration of their interiors and exteriors, but by purchasing space on the poster area that lines every car. The show included work by 103 artists or teams of artists, each producing a design or designs to occupy 14 card spots on the IRT subway line. For one month, an officially sanctioned (thanks to the $5,060 paid for the space) work of art was displayed on one out of four IRT cars.

...I saw some of these anti-ads at work on the trains and I think every painter at work on one-shot canvases destined for collection should have seen the double takes, bafflement, and laughs the works brought to the riding public. Many of these were delightful posters, made even more so by their subway context. Subway riders often read the ads obsessively, occupying their eyes and minds with anything but their fellow passengers. This show was a wonderful relief from the hypnosis of these ads. Group Material had to pay for the space but they should have been paid to use it by the Transit Authority. A little art in public places might help cities' populations feel more like people.

"Subculture" poster design by Julie Wachtel

Subculture" poster design by Doug Ashford

"Subculture" poster design by Janet Koenig & Greg Sholette

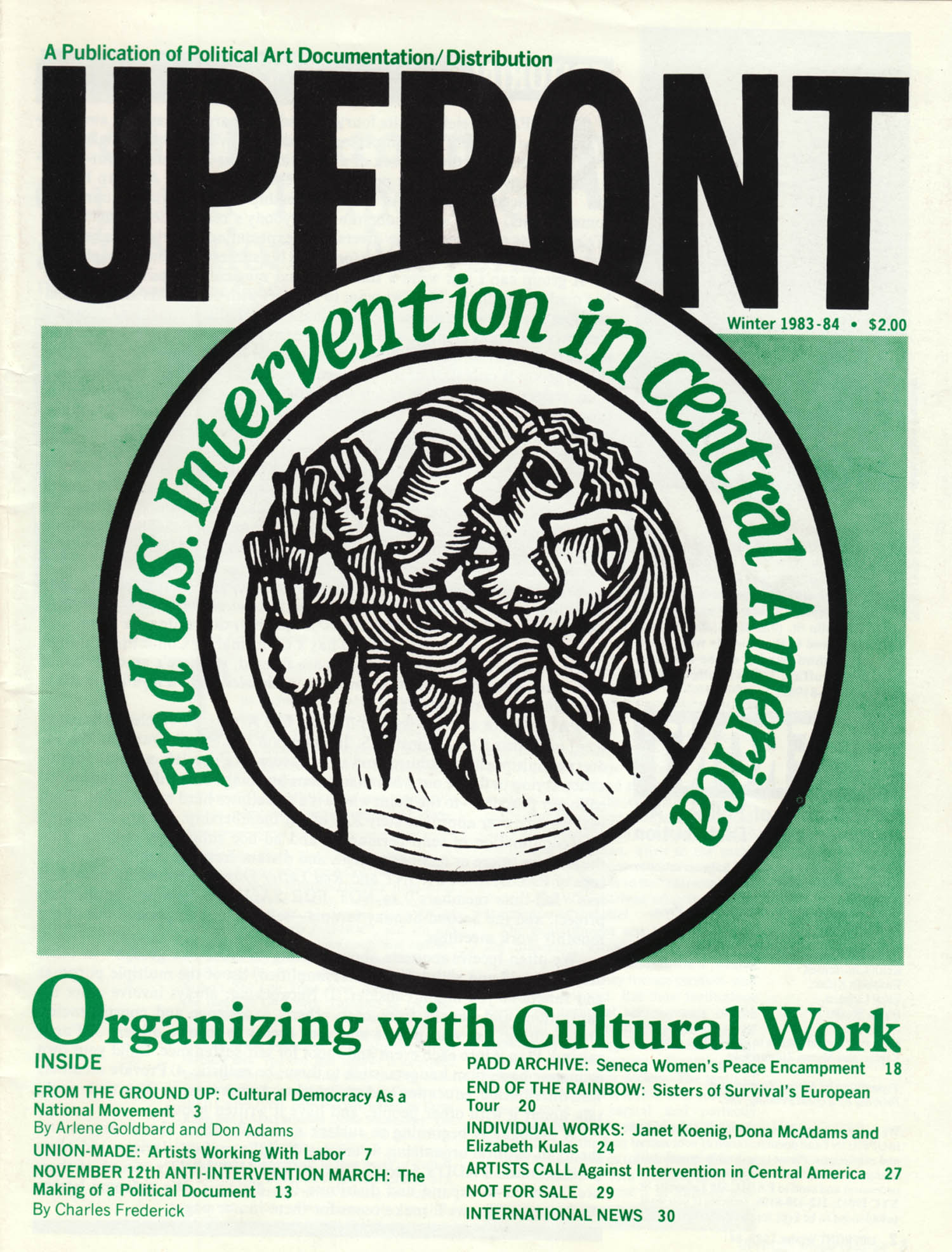

Political Art Documentation And Distribution (PADD)

PADD, Political Art Documentation and Distribution, began in 1979 as a discussion group with the goal of showing the effectiveness of image making in the political process. PADD brought together politically committed artists from veteran groups like the Art Workers Coalition and Fluxus, as well as from younger organizations like the Heresies collective, and Group Material. Lucy Lippard, Irving Wexler, and Greg Sholette were some of the key early participants. Unlike No Rio, Fashion/Moda and the early Group Material, PADD never maintained an art space. Instead, they promoted politically oriented art and performance through their publications, the magazine Upfront and the Red Letter Days Calendar; sponsored lectures and presentations; and assembled a large archive of political art (much of which is now part of the Museum of Modern Art library). The group also organized exhibitions in response to specific issues and political events in different venues, including No Rio. Keith Christensen, a member of PADD and the art director of Upfront, worked closely with Alan and me as the designer of the ABC No Rio book. The art critic Lucy Lippard was both a mentor and critic of No Rio; her high principles about art and politics were respected but not easily followed. She frequently reviewed No Rio shows in the Village Voice, and at Alan’s request wrote the preface for the ABC No Rio book.

Statement

By PADD, Upfront, 1984

Poster for PADD slide show uses collaborative design by Sue Coe and Anton Van Dalen

PADD is a progressive artists' resource and networking organization coming out of and into New York City. Our goal is to provide artists with an organized relationship in society, to demonstrate the political effectiveness of image making. One way we are trying to do this is by building a collection of documentation of international socially concerned art. The PADD Archive defines social concern in the broadest sense: any work that deals with issues ranging from sexism and racism to ecological damage and other forms of human oppression. The PADD Archive documents artwork from movement posters to the most individual of statements.

PADD is also involved with the production, distribution and impact of progressive art in the culture at large. We sponsor public events, actions and exhibitions. These are all means of facilitating relationships between (1) artists in or peripherally in, or not at all in the art world, (2) the local communities in which we live and work, (3) Left culture, and (4) the broader political struggles.

We hope eventually to build an international grass-roots network of artist activists who will support with their talents and their political energies the liberation and self-determination of all disenfranchised peoples.